Your donation will support the student journalists of Patriot High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

The Invisible Battle of ADHD in Public Schools

Students with ADHD reflect on their experiences with virtual learning and the recent return to in-person learning

Feb 12, 2022

A student stares at their test, eyes scanning the page with strained and dry eyes. They take a deep breath and try their best to concentrate. However, the student’s eyes betray them as they begin to wander across the room. They analyze everything, their mind races, and their motivation starts to fleet away. Suddenly ten minutes have went by in an instant, yet they are still on question eight. This student, like many other students around the world, has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). They aren’t ‘lazy’ or ‘apathetic,’ they are simply wired differently than their peers.

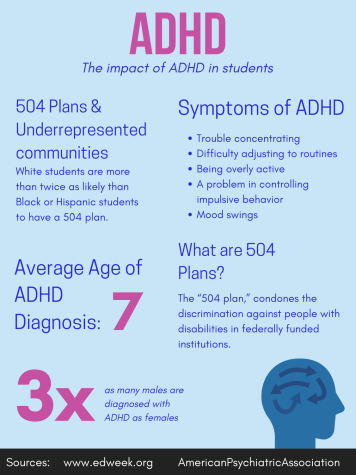

ADHD is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that is usually diagnosed during childhood and continues throughout the entirety of one’s life. While there are a wide variety of symptoms that are still being studied in present day, the most common and major ones include trouble concentrating, difficulty adjusting to routines, being overly active, a problem in controlling impulsive behavior, and mood swings.

As schools shifted from virtual to in-person learning, many students found it difficult to transition to the new routine. This extreme yet swift transition was especially challenging for teenagers with cognitive learning disorders, such as ADHD.

Rowan Newell (‘22) who was diagnosed with ADHD last summer, reflected on the hardships of the previous virtual learning format.

“Just something about being at school made it easier to concentrate and get things done,” Newell said. “So once I was at home, it was hard to have that workspace and manage everything in my life. Everything is on the computer: games, friends, videos, the internet, and now suddenly schoolwork. It was easy to get distracted and fall into temptation.”

Even after the pandemic, students are still struggling with the transition to in-person learning. According to a study published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, students who have ADHD tend to have a harder time adjusting to new routines. The study listed that one of the common ADHD signs is “an acute difficulty in adapting to changing situations.”

Syd Perry (‘22) struggled with changing their whole routine from virtual learning to in-person learning.

“At first it took some time to get used to seeing everyone, especially after being isolated for so long,” Perry said. “My concentration was off and staying organized was difficult, especially after seeing that everyone else was already adjusting quicker than me, but I got through it by the middle of the first quarter. I did feel comfortable in the classroom again and I got back into my regular routine that I had before lockdown.”

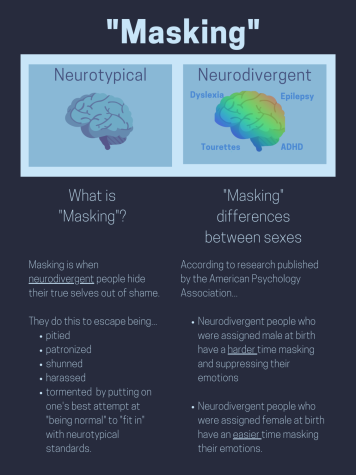

After returning to school, some students with ADHD felt the urge to begin ‘masking.’ Masking, otherwise known as ‘camouflaging,’ is a social survival strategy in the neurodivergent community where symptoms of neurodivergence are hidden in order to fit into neurotypical standards. The idea behind ‘masking’ is for neurodivergent people to appear more neurotypical and to avoid being ostracized.

Even though virtual learning created many obstacles for students with ADHD, there were still some benefits. Students were able to embrace their neurodiversity during virtual learning. With virtual classes, students with ADHD did not need to ‘mask’ their symptoms because everyone was more comfortable with one another and let their guards down. Unlike virtual classes, in-person instruction would no longer make it as easy to ‘blend in’ with other neurotypical students.

However, even with in-person classes, Perry did not feel the need to ‘mask’ neurodivergent symptoms. Perry returned to in-person learning and embraced their neurodivergent identity. Perry reflects on the immense change virtual learning had on accepting neurodivergent symptoms.

“I’ve actually learned not to mask as much anymore; we’ve all been through so much. We all let our guards down over virtual learning, we all went to class in our pajamas, we showed everyone our raw unfiltered selves over the camera online, and we bonded over that,” Perry said. “So, coming in person, not everyone cares as much anymore. Everyone is way more expressive and because of that it’s easier to not mask as much. I just embrace my neurodiversity. Especially as a neurodivergent LGBTQIA+ student, I’ve been a lot less afraid to hide myself because who cares?”

Newell also described how virtual learning made him feel more confident in himself and how he expressed himself because of online school.

“I didn’t have to hide myself as much virtually,” Newell said.

By learning about the experiences of other students with ADHD during the pandemic, it has become transparent that students need more support from schools. The system is not accommodating for students with ADHD, especially in an environment where temptations and distractions are always whispering. Teachers need to educate in a format that is ADHD friendly. The current structure is ineffective and students with ADHD are unfavorably affected.

With unrealistic deadlines and time constraints, confusing lesson plans for neurodivergent students, faulty standardized testing methods, and 504 plans which have not been updated since they were introduced in 2008, schools need to do better in assisting students with ADHD.

Since some schools have returned back to in-person learning, the education system must prioritize the needs of students with disabilities. This can be done by improving the implementation of 504 plans in public schools. The 504 plan condones the discrimination against people with disabilities in federal institutions. It does not have specific funding sources to support students, which means that it is up to states and school districts to decide. Therefore, this leads to disparities in services.

Schools must execute 504 plans in an equitable manner, emphasizing attention to the needs of disabled students-of-color and low-income students. For instance, according to a study, White students are more than twice as likely as Black or Hispanic students to have a 504 plan.

These inequities are connected to the advantages of families that can attain professional assistance and spend money advocating for 504 services. A study examining students with (ADHD) found that children from low socioeconomic backgrounds had a less likelihood of having 504 plans. This shows a racial and economic disparity in services that needs to be bridged. It is also suggested in data that 504 plans are easier to obtain at wealthier and whiter schools. If a school does not investigate a student suspected of requiring a 504 plan, help may only be provided after litigation and parental intervention, which takes resources and money.

The school system needs to be adjusted to accommodate students with ADHD, and the pandemic further emphasized this observation. Public schools should invest in counselors, school therapists, psychologists, and other mental health supports. Instead of leaving students with ADHD to struggle in a school system not designed for them, schools should accommodate the needs of neuroatypical students. This can be done by varying learning environments, implementing neurodiversity training for teachers and staff, and eliminating distractions in the classroom.

Like Newell said, “the only masking neurodivergent students should be doing is to protect themselves from COVID-19, not from social situations,” and if students are finally starting to accept their neurodivergence, then the school system should too.

Anonymous • Feb 13, 2022 at 7:06 pm

Awesome article