Imagine for a moment you live in a world where everything is not as it seems, a realm woven together by threads of suspicion, intrigue, and hidden agendas. While Hollywood may portray conspiracy theorists as “tinfoil hat-wearing,” crazed individuals, the truth that presents itself is far more nuanced than at first glance.

Occam’s Razoring Conspiracy Theorists

In a 2022 episode of the Dropouts Podcast, Neil deGrasse Tyson, a Harvard University graduate in Physics and a Ph.D. holder in Astrophysics from Columbia University, said “The anatomy of a conspiracy theorist is they already know what must be true in their own mind and wherever there’s a gap in the data they have to say its a cover-up.”

While not formally educated in the psychological sciences, Tyson holds a unique perspective on the human mind, often combating skeptics and naysayers who deny the scientific realities of space and space exploration. To his credit, however, a conspiracy theory differs from a regular theory in this exact way.

It begins with a thought or preconceived notion in the mind of an individual about a particular time, situation, or event. It serves as a means of explanation for a person, most often suggesting secretive or malevolent intentions behind these events.

Unlike their mainstream counterparts, major conspiracy theories aren’t as modern as one might be led to believe. In fact, historians have written records of conspiracy theories about the death of Alexander the Great from some 2,300 years ago. [photo]

The sheer prevalence of these beliefs in the lives of people around the world often prompts the logical follow-up question—why exactly do we believe what we believe?

Psychological & Epistemological Bases Of Conspiracy Theories

According to David A. Truncellito, a peer-reviewed epistemologist at the Internet Encyclopedia of Psychology, “When one forms a belief, one is seeking a match between one’s mind and the world. We sometimes, of course, form beliefs for other reasons – to create a positive attitude, to deceive ourselves. . . “

In essence, we believe what we believe because that’s what brings us the most comfort and understanding of the world around us.

Even acknowledging this fact, many industries such as Hollywood, particularly in their older movies, tend to portray conspiracy theorists as “mad hatters.” Despite this, understanding the psychological factors involved can shed light on what truly goes on in the mind of a conspiracy theorist.

Syed Zaidi, a prospective neuroscience student at UVA heath provides insight into the psychological aspects of those who believe in conspiracies.

Zaidi explains that individuals who believe in conspiracy theories tend to derive their notions of reality from a “hodge-podge” of differing worldviews and filter out the ones that are, in their minds, wrong or invalid.

He further discusses how individuals who hold onto conspiracy theories, especially those that can neither be proven nor disproven, tend to have their beliefs influenced by social threats, as supported by an article from the American Psychological Association.

A social threat, simply put, refers to situations where individuals feel that their social relationships or social standing is in jeopardy or at risk of collapse. This leads many to fall victim to the psychological pressures of group polarization.

Ingroups & Social Dynamics

Group polarization specifically refers to the tendency for individuals to adopt more extreme views when they are surrounded by a group of people who tend to think in the same manner.

Zaidi gave the example of fans rooting for their favorite sports icon, in this case Lionel Messi. Imagine that you’re watching a football match alone, you’ll probably have an enthusiastic response to your icon scoring a goal. However, when surrounded by hundreds of fans and a group of your friends at the field on game day, your reactions become increasingly fervent. You might find yourself screaming much louder and more enthusiastically as well as expressing yourself in ways you probably wouldn’t have otherwise.

This is a prime example of how individuals who believe in conspiracy theories often operate. With the advent of social media, the ability to curb irrational conspiracy theories became significantly more difficult because of the fact that they could spread so easily.

Promoting Critical Thinking & Questioning Everything (In A Productive Way)

It becomes evident that promoting critical thinking is essential in addressing these challenges. Conspiracy theories often gain traction because they offer what appears to be a logical conclusion or explanation of a situation, this reinforces their belief in being right simply because others tell them so.

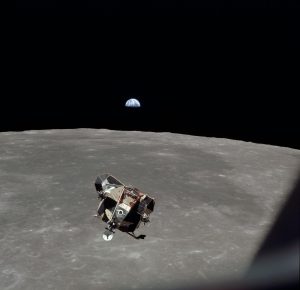

For instance, individuals who believe in the faking of the 1969 Apollo moon landing do so based on what they perceive as compelling evidence supporting their beliefs.

Many argue that the moon landing must have been faked or staged because, for example, there were no stars in the background of astronauts’ photos or that the U.S. flag appears to be waving in the wind on the surface of the moon. Despite these notions, there is a sound scientific explanation for each one.

Absence of stars in photos: The cameras used during the moon landing had settings optimized for bright lunar surface photography, which made capturing distant stars difficult because of the exposure settings and the brightness of the lunar surface.

Waving flag on the moon: The U.S. flag’s appearance of “waving in the wind” was due to the momentum it had when it was being unfurled by Astronaut Buzz Aldrin. The flag also appears extended because of a telescoping arm that was inside of the flag when it was erected on the lunar surface.

Strategies for debunking conspiracy theories go far beyond simply disproving them—they involve cultivating a mindset that values skepticism, evidence-based reasoning, and media literacy.

Whether or not you believe in conspiracy theories as a joke, a personal conviction, or a plausible reality, diving into the intricacies of the human mind the very way we think is truly captivating. Exploring the complexities of belief systems, means of critical thinking, and the psychology behind conspiracy theories offers some insights into how we perceive and interpret the world around us.

Vishu Sundaram • May 9, 2024 at 7:50 pm

This is a nice way to explain some psychology concepts to the average reader through a widespread problem. I especially like how you include tangible examples(like soccer fans and moon landing conspiracies) to illustrate these concepts. However, with that being said, I do tend to disagree with Neil DeGrasse Tyson’s views on many things as he sometimes goes past the level of “healthy” skepticism and turns into a radical skeptic who criticizes everything simply for the sake of criticizing it and not productively as you suggest.